The science behind PRISM

It is important to stress that PRISM Brain Mapping and traditional psychometric instruments stem from two different sciences and direct comparison is akin to comparing apples and oranges; they have some factors in common, but also fundamental differences.

Unlike many psychometric instruments, PRISM is not based on a theory developed by any one person. It represents a simple, yet comprehensive, synthesis of research by some of the world’s leading neuroscientists into how the human brain works, and why people, who have similar backgrounds, intelligence, experience, skills, and knowledge, behave in very different ways. The instrument’s graphical representation of the human brain serves, not only to remind people of its biological basis, but also to help demonstrate the equally valuable merits of specific cerebral modes.

The role of neuroscience – and PRISM – is to explain behaviour in terms of the activities of the brain. How the brain marshals its billions of individual nerve cells to produce behaviour, and how these cells are influenced by the environment.

At the root of the PRISM, Brain Mapping instrument is the basic fact that all behaviour is brain-driven. Each person has his or her own way of looking at the world (perception) and responding to it (behaviour). Those recurring responses – part inherited and part learned – fall into patterns, referred to as behaviour preferences. Each person exhibits his or her own personal behaviour preferences to a great extent by how and what they say and do. Much like a successful company, the brain relies on the input of its various parts prior to making a decision. That is, the brain acts as a set of collaborating brain regions that operate as a large-scale network.

In order to understand our behaviour it is necessary to consider the make-up of the brain. For decades psychologists maintained that once the brain’s physical connections were completed during childhood, the brain had become hardwired and remained like that for life. Now, thanks to the latest imaging technologies, the concept of ‘neuroplasticity’ (the brain’s ability to change), and brilliant clinical research, we see that this is, in fact, not the case and that human development is a continuous, unending process.

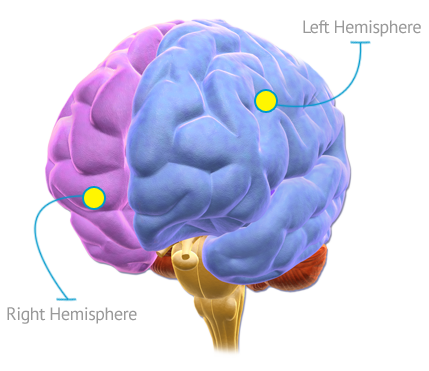

PRISM looks at the structure and function of the brain, and especially at the differences between the brain’s hemispheres, not only in terms of attention and flexibility, but in attitudes to the world. It is a well-established fact that there are obvious, undisputed differences in the shape, size, neuronal architecture, neurochemistry and neuropsychology of the brain’s two hemispheres. It seems obvious to ask: what does all that mean? The difference lies not in what they do, but how they do it.

The processes required to perform exact calculations reside in the left hemisphere, in the parietal lobe. A different region of the brain, in the right hemisphere, underlies approximation of number. People generally show high correlations between mathematical ability and spatial ability in aptitude tests. In other words, people who have very good spatial ability – who have a good sense of direction – often, but not always, have good mathematical skills as well.

Also, the right hemisphere is unable to identify written numerals such as ‘12 – 6′. The right hemisphere knows that 6 is less than 8, but this knowledge completely disintegrates for the word ‘six’. Neither can the right hemisphere alone name digits and perform arithmetic.

Also, the right hemisphere is unable to identify written numerals such as ‘12 – 6′. The right hemisphere knows that 6 is less than 8, but this knowledge completely disintegrates for the word ‘six’. Neither can the right hemisphere alone name digits and perform arithmetic.

The left hemisphere can add up numbers 2 plus 2, but the brain finds this impossible if the sum is shown solely to the right hemisphere. The left hemisphere can do multiplication whereas the right hemisphere cannot. The right hemisphere approximates while the left hemisphere calculates.

Similarly, although language resides in the left hemisphere in most people for people who are right-handed, it is not usually the case for left-handers – language is normally housed in both hemispheres in these people.

Fundamentally, PRISM is about our attention to the world; how we see and respond to our environment, including the people in it. More accurately, it is about our perception, or representation, of our environment. Our attention can either be broad or narrow.

The right hemisphere is responsible for broad attention, the left hemisphere for narrowly focused attention. Although the brain is split into hemispheres, it is a single, integrated, highly dynamic system. Events anywhere in the brain are connected to, and potentially have consequences for, other brain areas. As you read the words on this page, you are using thousands of the 100 billion nerve cells that make up your brain. The electrical firings and chemical messages running between these cells, called neurons, are what produce our thoughts, feelings and interactions with the world around us.

The PRISM Model is a metaphor for how the brain’s functional architecture and neural networks interact with brain chemicals such as glutamate, dopamine, noradrenaline, serotonin, testosterone, and oestrogen to create behaviour. Modern neuroscience rests on the assumption that our thoughts, feelings, perceptions, and behaviours emerge from electrical and chemical communication between brain cells.

On a broad level, the brain lends itself to partitioning, based largely on its anatomy. All proposed divisions within the brain are, however, highly artificial and are created in response to the human need to separate things into neat, easily understandable units. We must always bear in mind, however, that the brain functions as a whole and, with that caveat in mind, the PRISM quadrant model provides us with a useful schema that we can refer to when we are visualising how our brains are organised. It is, therefore, based on scientific principles and facts which have been simplified into a workable model to facilitate understanding.

PRISM is intended to be a sort of beginner’s guide to neuroscience. The neuroscientific language about the brain is extremely complex. PRISM attempts, therefore, to simplify that language so that it can be more easily understood. As a result, it contains many simplifications. For example, when we say; the left hemisphere is responsible for this, or the right hemisphere is responsible for that, it must be understood that in any one human brain at any one time both hemispheres will be actively involved. No single part of the brain does solely one thing and no part of the brain acts alone. All our thoughts, emotions and actions are the results of many parts of the brain acting together. When reading this section, it is important to bear in mind that the brain functions as the result of the dynamic interaction between many different systems, at different levels of organization, each operating according to its own rules.

The adult brain weighs about 3 pounds (1.4 kg) and contains about one trillion brain cells, 100 billion of them neurons. Neurons have both short and long fibres that contact the bodies of other neurons, and there are about one million billion connections between cells in the brain.

The number of connections in the human brain is much bigger than the whole earth’s population…about 7 billion.

Most of who we are is the result of the interaction of our genes and our experiences. In some situations the genes are more important, while in others the environment is more crucial. Genes set boundaries for human behaviour, but within these boundaries there is immense room for variation.

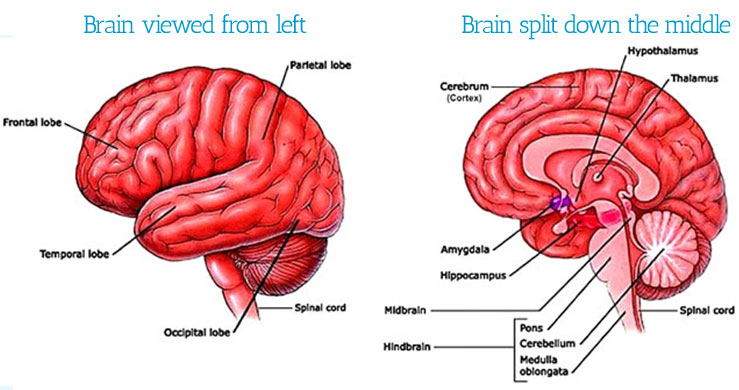

The brain is split down the middle from front to back into two blocks known as hemispheres. The left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controls the left side of the body.

While it is true that one hemisphere dominates over the other in terms of our experience of the world and our actions, both sides of the brain work together in almost all situations, tasks and processes. In other words, people are not right or left brained, they use both sides of the brain.

When we consider large sections of the brain, we need to consider them as systems – not dichotomies. A system has inputs and outputs, and a set of component parts that work together to produce appropriate outputs e.g. behaviours. The differences between the right and left hemispheres are subtle, and simple, black and white dichotomies referred to in the ‘popular’ media do not explain accurately how the two sides function.

The two hemispheres are linked by a ‘bridge’, known as the corpus callosum has an ‘excitatory’ function i.e. it enables the two hemispheres to communicate with each other. However, the main purpose of a large number of these connections is actually to inhibit – in other words to stop the other hemisphere interfering inappropriately. The corpus callosum’s excitatory and inhibitory roles are, therefore, both necessary for normal human functioning.

Each hemisphere can be divided into four individuals chunks, known as lobes. The lobes are called frontal (front), temporal (side), parietal (top), and occipital (back). The right hemisphere (Green and Blue on the PRISM model) is predominantly associated with empathy and novelty. The left hemisphere (Gold and Red on the PRISM model) is predominantly associated with systemizing and routine.

‘Empathizing’ is the drive to identify another person’s emotions and thoughts, and to respond to them with appropriate emotion. For example, the right hemisphere helps us pick up on nonverbal cues in speech and gesture as well as in facial expressions. ‘Systemizing’ is the drive to analyse, explore and construct a system. Systemizing intuitively figures out how things work, or extracts the underlying rules that govern the behaviour of a system.

The right hemisphere is interested in others as individuals. Self-awareness, empathy and identification with others are largely dependent upon the right hemisphere. On the other hand, the left hemisphere is not impressed by empathy. Its concern is with maximising gain for itself and its driving value is practical usefulness.

The left hemisphere is competitive and its concern, its prime motivation, is power. The right hemisphere is particularly well equipped to deal with passions, sense of humour, metaphoric and symbolic understanding, and all imaginative and intuitive processes.

While a lot of attention has been focused in the press on the interaction between the right and left hemispheres, it is also important to focus on the interaction between the front and the back of the brain. The back of the brain (Red and Blue on the PRISM model) is the sensory or input half, which receives input from the outside world and sorts, processes, and stores all of our sensory representations. This area is, however, not simply a site for processing sensory information. It is also the region of cortex for associative processes, where information from the various senses is bound together for higher order processing.

The PRISM model also divides the cortex horizontally into two levels; the dorsal cortex and the ventral cortex. The dorsal cortex comprises the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex – the larger and upper part of the frontal lobe – the whole of the parietal lobe, the motor areas and the anterior cingulate cortex. The ventral cortex comprises the temporal and occipital lobes, the lower parts of the frontal cortex and the ventromedial frontal cortex.

The dorsal cortex formulates and executes plans whereas the ventral cortex classifies and interprets incoming information about the world. In essence, creating and carrying out plans is the responsibility of the dorsal cortex, whereas the ventral cortex is largely concerned with processing inputs from the senses and using them to activate the relevant memories about relevant objects or events. The two levels always work together. For example, the top half uses information from the bottom half to formulate and modify its plans as they develop over time.

It is important to bear in mind that habitual behavioural preferences generally should not be related to intelligence. Intelligence is the ability to understand complex data and solve difficult problems. People who have a preference for one or more behavioural preferences can be anywhere on a scale between highly intelligent and not very intelligent. The PRISM behavioural dimensions are about how you approach and interact with other people and situations in your day to day life. Also, although you may have certain preferred behaviours, you will sometimes adopt different behaviours to enable you to cope more effectively with changes in your life.

We hope that PRISM Brain Mapping will be helpful to you in your journey to understand yourself and others.

We’re here to help!

Now experience PRISM Brain Mapping online or

By connecting with us on

| Phone : +91 9819 714 238 | Skype : PRISM Brain Mapping | ||

| WhatsApp : +91 9819 714 238 | Email : info@prismbrainmap.com |